Since 2004, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Ground Force, or PLA Army, has officially held the second position in China’s military modernization priorities, following the more technologically advanced naval, air, and rocket forces. This prioritization, while reflecting China’s shifting strategic focus towards maritime power, doesn’t diminish the critical role of the PLA Army. As the world’s largest standing army, it remains a cornerstone of China’s defense and evolving military strategy. While progress may appear slower compared to other branches, the PLA Army is undergoing a significant transformation, marked by organizational restructuring, advanced equipment adoption, and a renewed emphasis on joint operational capabilities. Even visual aspects, such as the Pla Army Uniform, are evolving to reflect this modernization.

Introduction: The PLA Army in China’s Modern Military Landscape

The late 20th century marked a pivotal shift in Chinese military thinking. Influenced by the technological prowess displayed during the First Gulf War and the strategic lessons of the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, China’s senior military leadership initiated a comprehensive modernization program for the PLA. This initiative, spearheaded by figures like Jiang Zemin, recognized the need for a leaner, technologically superior military with a stronger focus on maritime threats. While the PLA Navy and Air Force naturally took center stage in this new maritime-centric approach, the PLA Army, despite its continental significance, was slated for modernization, albeit at a measured pace.

The late 1990s witnessed an acceleration of PLA modernization, fueled by consistent double-digit percentage increases in the defense budget. This coincided with substantial manpower reductions within the PLA. President Jiang Zemin’s 1997 announcement of a 500,000 personnel reduction highlighted the changing priorities. The PLA, then estimated at 3 million personnel, saw the Army bear the brunt of these cuts, losing 18.6% of its manpower, while the Navy, Air Force, and Second Artillery experienced comparatively smaller reductions.

The 2004 Chinese defense white paper formalized this shift, declaring development priority for the “Navy, Air Force and Second Artillery Force,” emphasizing enhanced comprehensive deterrence and warfighting capabilities. This trend solidified in subsequent white papers, culminating in the 2015 declaration:

“The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests.”

This statement underscored the PLA Army’s repositioning within China’s military strategy. Despite this shift, the PLA Army remains crucial for maintaining territorial integrity, deterring regional threats, and contributing to joint operations. The ongoing reforms, including a further 300,000 personnel reduction announced in 2015, continue to reshape the PLA Army, aiming for a more agile, technologically advanced, and joint-capable force. This transformation is not just about equipment; it is also reflected in the evolving PLA army uniform and the overall professionalization of the force.

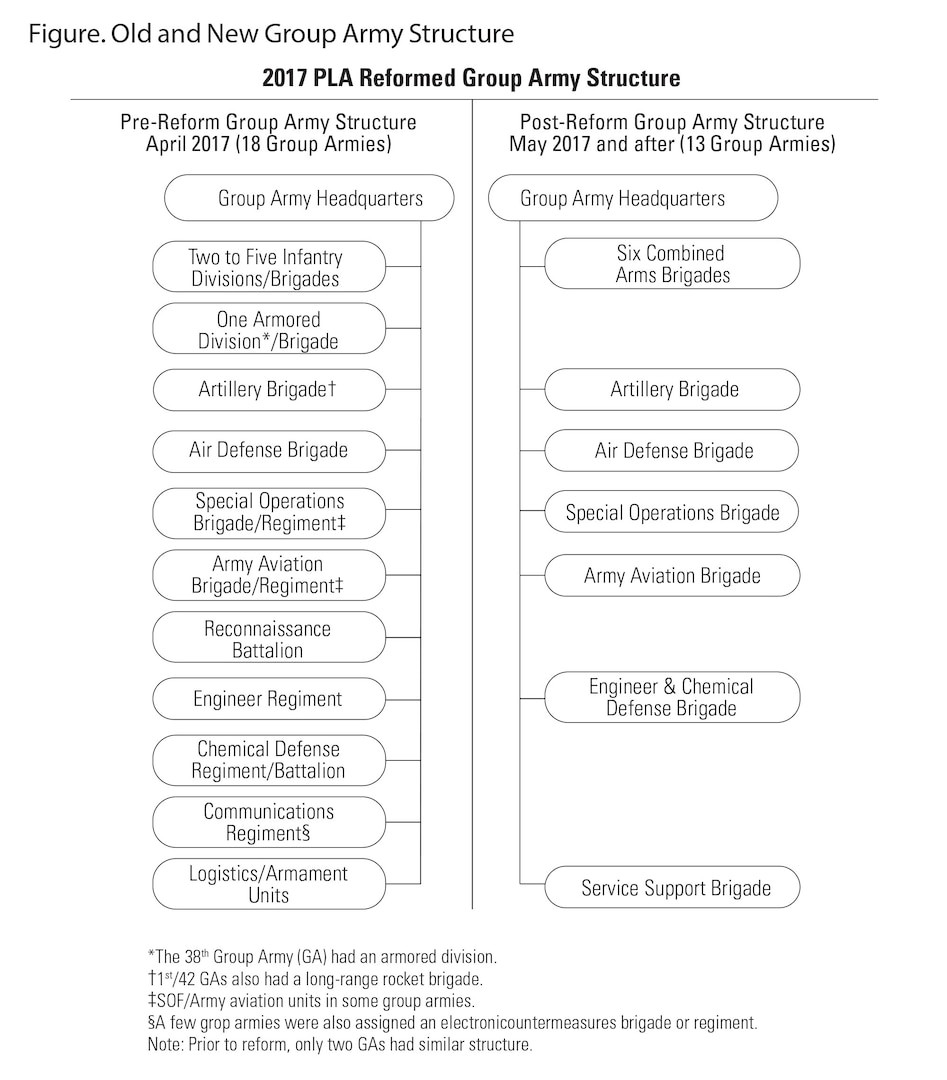

Figure. Old and New Group Army Structure

Figure. Old and New Group Army Structure

The Army’s New Headquarters and Leadership Structure

“The overall level of our military power system lags behind the world’s military powers. In particular, the Army’s modernization is relatively backward. Some problems are rather prominent. It is necessary that we downsize and optimize its structure, innovate its form, and strengthen its functions.”

—PLA Army Commander Li Zuocheng

The PLA’s traditional structure, with the four General Departments acting as a national army headquarters and joint staff, has undergone a significant overhaul. The dissolution of these departments and the expansion of the Central Military Commission (CMC) bureaucracy to 15 functional entities has redistributed power and responsibilities. For the PLA Army, this meant the creation of a dedicated national-level Army headquarters [陆军领导机构], placing it on par with the Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force in terms of service status.

This structural change has implications for command and control. The new Army headquarters must now coordinate with both the CMC for “army building” and the five Theater Commands (TCs) for operational deployments. This necessitates a complex staff organization capable of interfacing with both CMC and TC structures. The known structure of the Army headquarters staff includes:

- Army Discipline Inspection Commission

- Army Staff Department

- Operations Bureau

- Training Bureau

- Arms Bureau

- Army Aviation Corps Bureau

- Administration Bureau

- Border and Coastal Defense Bureau

- Planning and Organization Bureau

- Subordinate Work Bureau

- Army Political Work Department

- Organization Bureau

- Propaganda Bureau

- Cadre Bureau

- Soldier and Civilian Personnel Bureau

- Art Troupe

- Army Logistics Department

- Procurement and Supply Bureau

- Transportation and Delivery Bureau

- Health Bureau

- Finance Bureau

- Army Equipment Department

- Maintenance and Repair Support Bureau

- Aviation Equipment Bureau

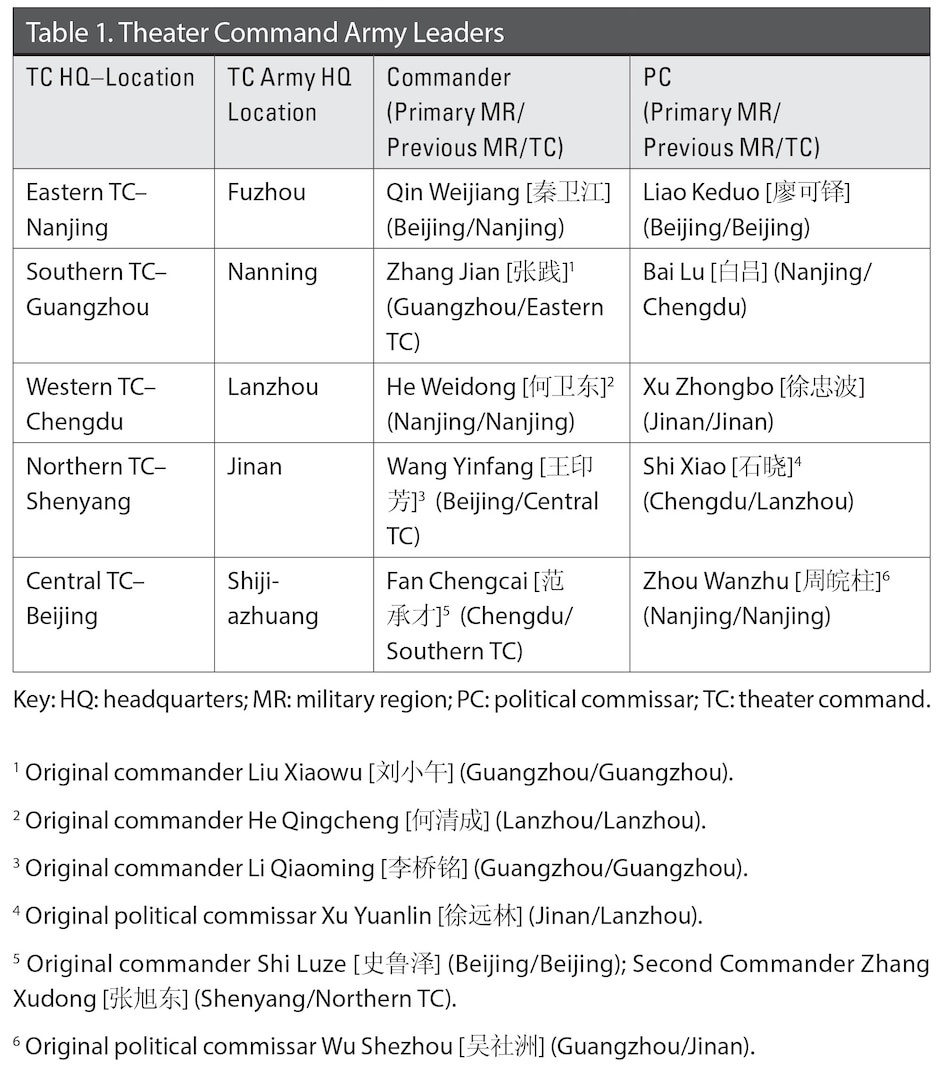

The establishment of joint TCs also introduced a new command level for the army: the TC Army headquarters [战区陆军机关]. These headquarters, at theater deputy leader grade, are crucial links in the chain of command, connecting operational units to both the Beijing-based Army headquarters and the regional joint TC headquarters. Interestingly, TC Army headquarters add a layer to the command chain, directly commanding operational army units within their area of responsibility, rather than the joint TCs themselves. This is highlighted by the fact that TC army units wear a generic army patch, replacing the former Military Region-specific patches.

Table 1. Theater Command Army Leaders

Table 1. Theater Command Army Leaders

TC Army headquarters are assigned four primary missions:

- Campaign headquarters for combat operations

- Component of the theater joint command post

- Construction headquarters for routine management

- Emergency response headquarters

This complex command structure, while aiming for greater efficiency and jointness, is still evolving. The PLA is working to refine these interactions and address potential complexities by 2020.

Army Order of Battle: Becoming Leaner and More Agile

“Force structure remains irrational; there are too many conventional units and not enough new types of combat forces. The proportion of various arms is not balanced; officers are out of proportion to enlisted personnel. Weapons and equipment are relatively backward.”

—Eastern Theater Army Headquarters Political Commissar MG Liao Keduo

The PLA Army has undergone significant personnel reductions, reflecting its shift towards a more technologically advanced and agile force. From an estimated 2.2 million in 1997, the army is projected to number less than half of the total PLA force of 2 million after the ongoing reforms. This reduction is not simply about numbers; it is about creating a more effective fighting force. Personnel assigned to new CMC staff, TC headquarters, and support forces are now accounted for separately, further streamlining the operational army.

The 2013 defense white paper emphasized the development of “new types of combat forces,” including army aviation, light mechanized units, special operations forces (SOF), and digitalized units. The aim is to create smaller, modular, and multifunctional units capable of air-ground integration, rapid deployment, and specialized operations.

Prior to the reforms, the PLA Army’s order of battle included 18 Group Armies and various independent units. In early 2017, this comprised approximately 21 divisions, 65 combat brigades, 12 army aviation units, and 11 SOF units. However, the “below-the-neck” reforms initiated in 2017 have drastically reshaped this structure.

The changes include:

- Reduction of Group Armies to 13, standardized and renumbered from 71 to 83.

- Combat divisions reduced to 6, with 15 former divisions reorganized into brigades.

- Transformation of all combat brigades into combined arms brigades [合成旅], increasing their number to around 82.

Each standardized Group Army now consists of six combined arms brigades and six supporting brigades, including artillery, air defense, army aviation (or air assault), SOF, engineer and chemical defense, and service support brigades. Combined arms brigades are categorized as heavy (armor or mechanized infantry) or light (light mechanized or mountain) and are structured around combined arms battalions. Xinjiang and Tibet Military Districts maintain non-standard structures, directly commanding combat and support units.

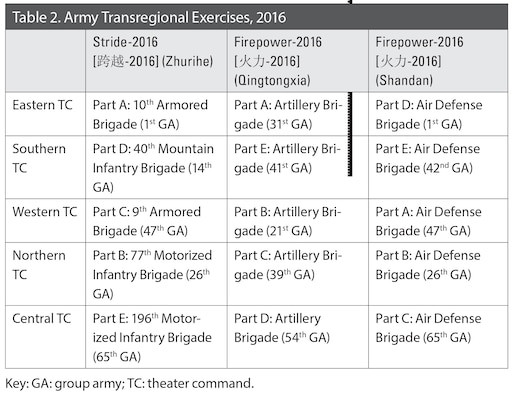

Table 2. Army Transregional Exercises, 2016

Table 2. Army Transregional Exercises, 2016

The reforms have significantly boosted “new-type combat forces,” particularly army aviation and SOF. Each Group Army and the Xinjiang and Tibet MDs now have an army aviation brigade. SOF brigades have also expanded to 16. Furthermore, the PLA Army has created four new marine brigades by transforming existing motorized infantry and coastal defense units, bringing the total to six marine brigades across the Theater Navies.

These organizational changes reflect a move towards a more flexible, modular, and specialized PLA Army, capable of meeting the demands of modern warfare. This modernization is also visible in the PLA army uniform, with new camouflage patterns and equipment designed for diverse operational environments.

Army Equipment and Battalion Staff Developments: Modernizing the Arsenal

“Many military units are still upgrading equipment; the problem of new and old equipment “three generations living under one roof” is relatively prominent.”

While personnel numbers have decreased, the PLA Army is undergoing a comprehensive equipment modernization program. This includes new PLA army uniforms and personal equipment, alongside advanced tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, helicopters, UAVs, and small arms. However, due to the sheer size of the PLA Army and production capacity, this modernization is a phased process. Notably, the PLA Army, being second in priority, doesn’t always receive the most cutting-edge equipment.

For example, the Type-96B main battle tank, not the more advanced Type-99 series, has been designated as the “backbone” of China’s tank force. While capable, this highlights the tiered approach to modernization. Despite advancements, a significant portion of the PLA Army’s armored force still consists of older models, a condition known as “three generations under one roof.” Xi Jinping’s goal of equipment modernization by 2035 aims to mitigate this issue by phasing out older equipment and increasing the proportion of newer models.

New technologies are enhancing the PLA Army’s capabilities: increased mobility, longer firing ranges, and better integration with other services. Army commanders now have access to a wider range of offensive assets, including long-range artillery, attack helicopters, SOF, electronic warfare capabilities, and support from the PLA Air Force and armed UAVs. Advanced reconnaissance and surveillance systems further enhance target acquisition.

These advancements, however, place greater demands on commanders and staff, particularly at the battalion level. Recognizing this, the PLA Army is expanding battalion staffs to include a deputy battalion commander, battalion master sergeant, chief of staff, and four staff officers. These staff officers specialize in:

- Operations and reconnaissance

- Artillery/firepower and engineering

- Information and communications

- Support

This enhanced battalion staff structure is designed to improve command and control in combined arms operations and effectively utilize the new technologies being deployed. These changes are also reflected in training and education programs, ensuring personnel are prepared for these new roles.

Recent Training and Other Deployments: Sharpening the Sword

“Solving the “Five Cannots” and improving command combat capabilities is an urgent task in strengthening training and preparing for war.”

The PLA acknowledges a “large gap” between its current training level and the demands of modern combat. A key objective is to enhance the realism of training and combat formalism and cheating, a long-standing goal reiterated by senior PLA leaders. Despite progress, the PLA recognizes deficiencies in advanced, integrated joint operations capabilities.

The core of the training challenge is seen as a leadership issue, particularly at battalion level and above. The PLA emphasizes “training officers first” to address shortcomings identified as the “Two Inabilities” and “Five Cannots”:

- Five Cannots: Some commanders cannot:

- Judge the situation

- Understand higher authorities’ intentions

- Make operational decisions

- Deploy troops

- Deal with unexpected situations

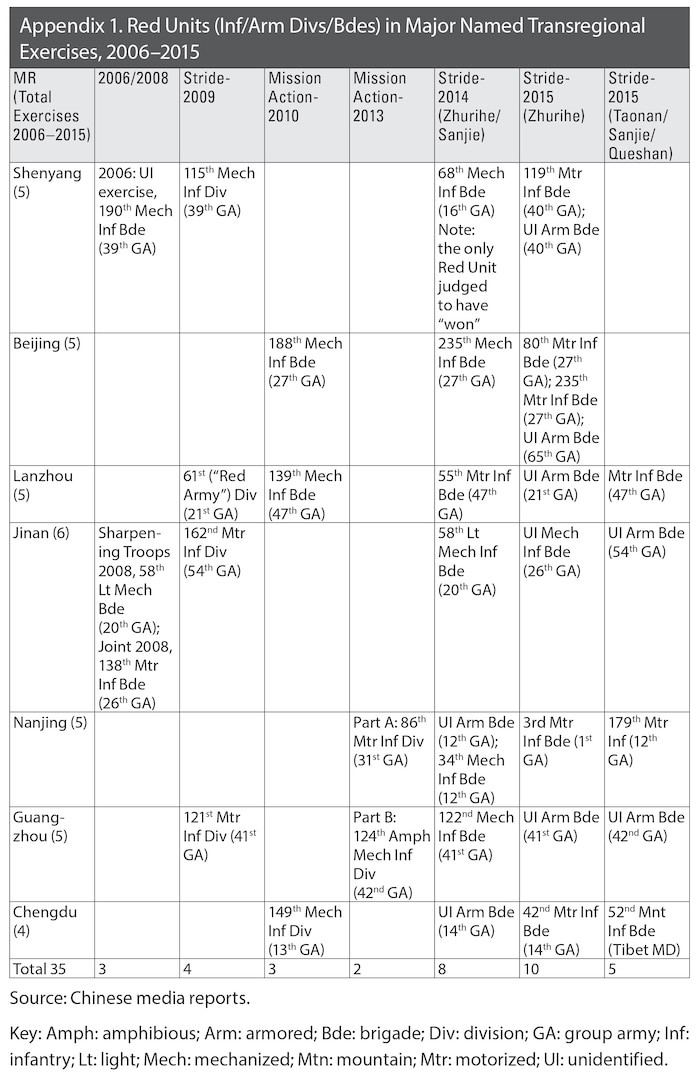

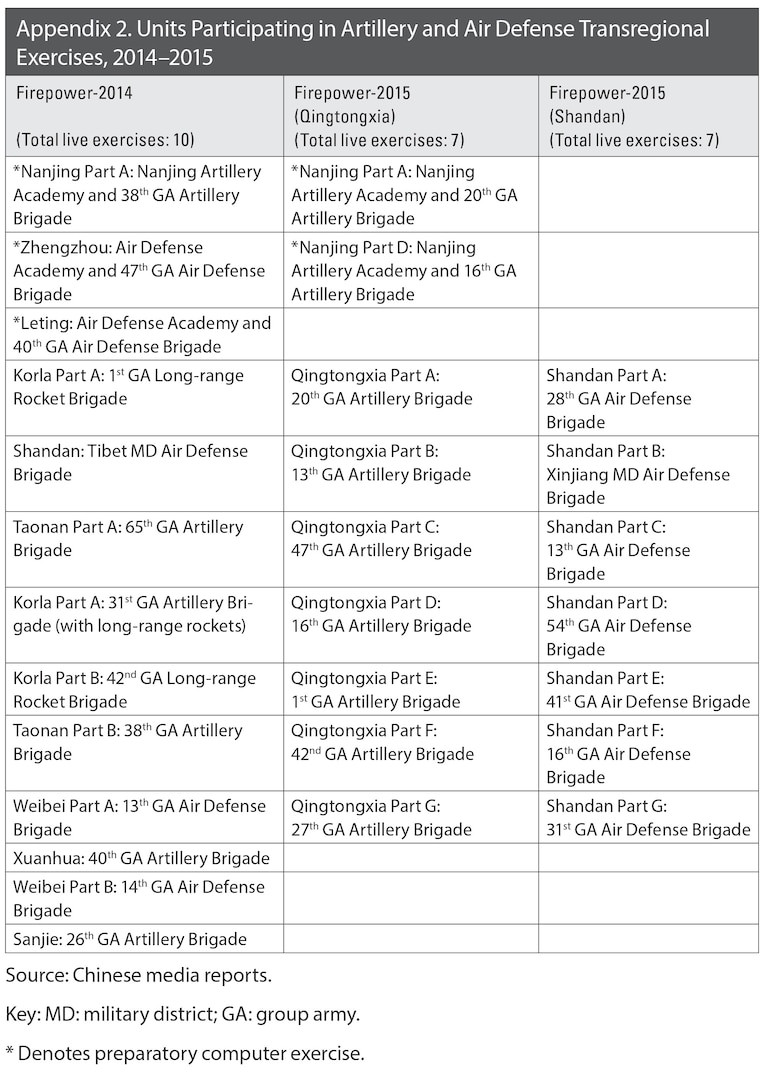

Transregional exercises [跨区演习] have been a crucial tool in reforming operational thinking. These exercises, numbering around 74 from 2006 to 2016, involve units deploying to distant training bases, often facing simulated enemy engagements (“blue force”). They test adaptability, command and control, and joint interoperability.

Appendix 1. Red Units (Inf/Arm Divs/Bdes) in Major Named Transregional Exercises, 2006–2015

Appendix 1. Red Units (Inf/Arm Divs/Bdes) in Major Named Transregional Exercises, 2006–2015

Key exercise series include Stride and Firepower. Notably, no “red force” (friendly) unit consistently defeats the “blue force” in these exercises, mirroring the U.S. Army’s National Training Center experience, highlighting areas for improvement. In 2016, exercises specifically targeted the “Five Cannots” and aimed to improve new-type combat forces and joint operations capabilities.

Besides transregional exercises, the PLA Army engages in regional exercises, joint training, and international military competitions. Participation in events like the International Army Games in Russia demonstrates a commitment to improving performance and interoperability.

United Nations Peacekeeping Operations (UN PKO) also provide valuable real-world experience. The PLA Army has contributed engineer, transport, medical, and even infantry units to various UN missions, offering opportunities for leadership development, logistics, and operational experience in diverse environments.

Appendix 2. Units Participating in Artillery and Air Defense Transregional Exercises, 2014–2015

Appendix 2. Units Participating in Artillery and Air Defense Transregional Exercises, 2014–2015

These diverse training and deployment activities are crucial for transforming the PLA Army into a modern, combat-ready force. Even the PLA army uniform, with its improved camouflage and functionality, plays a role in enhancing soldier effectiveness in diverse operational settings.

New Logistics Arrangements: Streamlining Support

“The traditional support model of our army is weak, with specialties not unified, backward technologies, and scattered resources making it difficult to complete system support tasks based on information systems.”

The PLA Army is revamping its logistics system to enhance efficiency and integration. Historically, separate Logistics and Armament Departments led to inefficiencies at lower command levels. In 2012, the PLA merged these departments at division and brigade levels into a unified Support Department [保障部]. This consolidation has extended to Group Armies and TC Army headquarters. Furthermore, each Group Army now has a service support brigade integrating logistics, maintenance, communications, UAV, and electronic warfare units.

A major shift is the creation of the CMC Joint Logistics Support Force [中央军委联勤保障部队] in 2016. This “force” comprises the Wuhan Joint Logistics Support Base and five joint logistics support centers across the TCs. It consolidates many functions of the former joint logistics sub-departments, aiming for centralized and efficient support.

The Joint Logistics Support Force is responsible for general-purpose materials and equipment, while specific arms and services handle specialized support. Its focus areas include finance, housing, uniforms, food, transportation, and hospitals. The PLA Army retains its own logistics systems for service-specific needs, creating a layered support structure. These changes aim to address the fragmented and inefficient logistics model and create a more responsive and integrated support system for modern operations.

Changes in Doctrine and the Education System: Adapting the Mindset

“[Military reform] must address the shortage of officers who have a deep knowledge of joint combat operations and advanced equipment… In some cases, soldiers lack knowledge and expertise to make the best use of their equipment.”

The PLA Army’s modernization necessitates adjustments to doctrine and the education system. The shift towards joint operations and advanced technologies requires a new generation of officers and NCOs with specialized skills and a joint-oriented mindset.

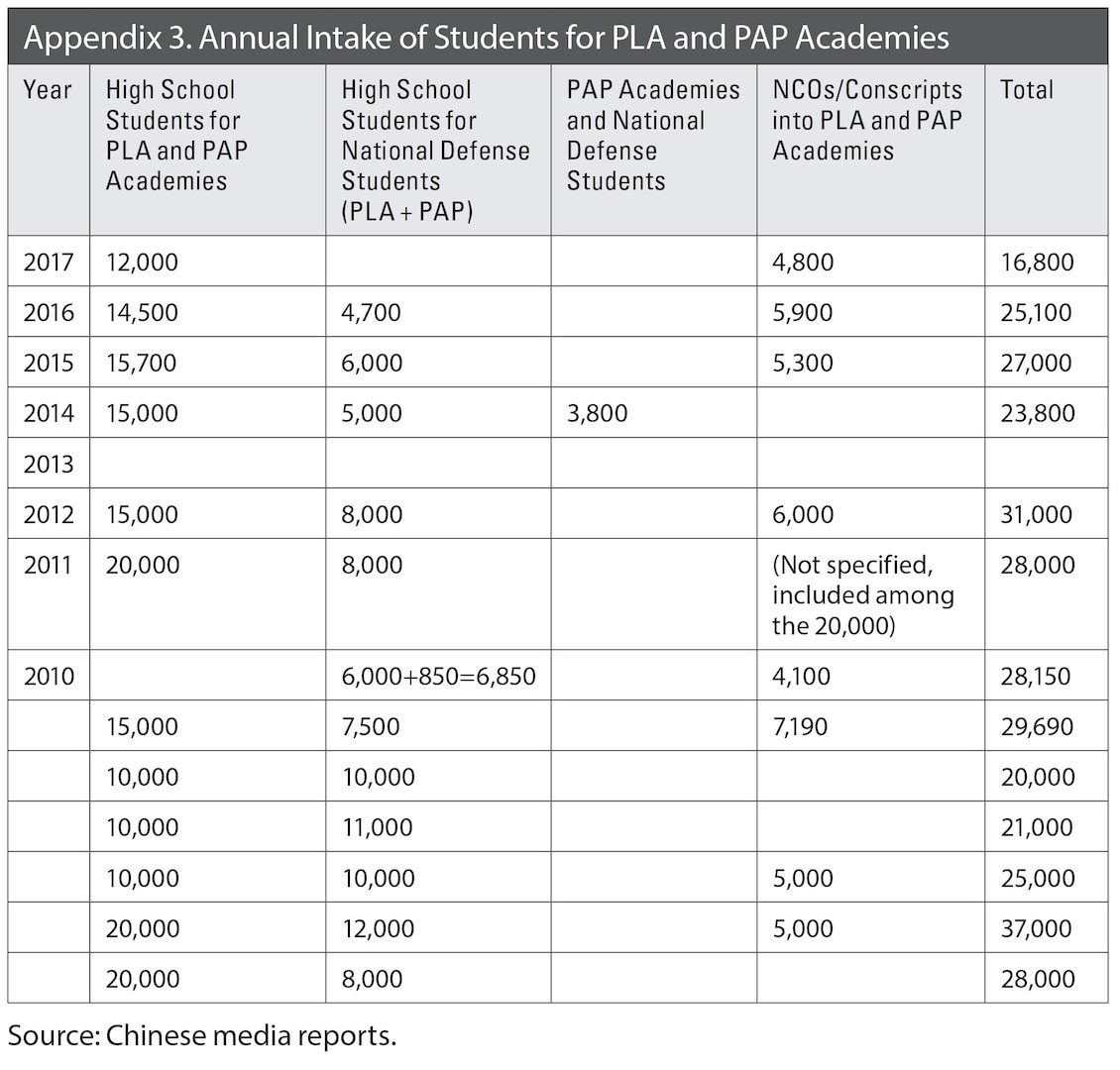

Personnel reductions are impacting the officer corps, with projections suggesting half of the 300,000 cuts will affect officers. Consequently, cadet intake at PLA academies has been reduced. The National Defense Student program is also being revised to recruit graduates from civilian universities, allowing for more targeted recruitment based on specific skills and needs.

Appendix 3. Annual Intake of Students for PLA and PAP Academies

Appendix 3. Annual Intake of Students for PLA and PAP Academies

The PLA is also reorienting educational priorities. Enrollment in army-related fields like infantry and artillery is decreasing, while fields like aviation, missile technology, and maritime studies are expanding. Areas with “urgent needs,” such as space intelligence, radar, and drones, are also receiving increased focus. Similarly, graduate student enrollment is being reduced and refocused on military-related fields aligned with new-type combat forces.

Curricula in PLA academies are being revised to emphasize joint operations and the integration of advanced technologies. Training programs at all levels are being adapted to prepare officers and NCOs for combined arms and joint operations. This includes focusing on staff procedures and decision-making in technologically complex environments.

These changes aim to shift the PLA Army’s institutional mindset from a “Big Army” [大陆军] approach to a modern, joint-capable force. This transformation requires time and sustained effort to overcome deeply ingrained organizational cultures and practices.

Conclusion: A Force in Transition

“Improving the army’s combat strength has become a major focus. But the modernization level of the Chinese army is inadequate to safeguard national security, and it lags far behind advanced global peers. The Chinese army is not capable enough of waging modern warfare, and officers lack command skills for modern warfare.”

Despite visible progress, including new equipment, exercises, and even the modernized PLA army uniform, the PLA Army acknowledges it is still in a phase of transition. Self-critiques within the PLA media highlight persistent shortcomings in operational capabilities, particularly in joint operations and command proficiency. While tactical proficiency at lower levels may be improving, integrating units into effective combined arms teams at battalion level and above remains a key challenge. The PLA aims to transform “strong fingers” (individual units) into a “hard fist” (combined arms/joint operations).

The “below-the-neck” reforms and the creation of combined arms brigades and battalions are steps in the right direction. However, effective implementation requires well-trained commanders and staff capable of leveraging these new structures and technologies. The PLA Army is actively addressing these issues through ongoing reforms in training, education, and doctrine.

As the PLA Army modernizes, it is also seeking to define its role in China’s evolving maritime-focused military strategy. New-type combat forces like helicopter units, SOF, and long-range artillery are being adapted for operations beyond China’s landmass, contributing to joint maritime and aerospace campaigns. However, strategic lift capabilities remain a constraint for deploying larger formations over long distances, although investments in transport aircraft and amphibious ships are underway.

The PLA Army is undergoing a profound transformation, accepting a potentially secondary role in China’s overall military modernization compared to the naval and air forces. This requires a significant shift in institutional mindset and a sustained commitment to reform. The PLA Army’s journey to becoming a truly modern and joint-capable force is ongoing, and its success will be crucial for China’s evolving national security strategy. The evolving PLA army uniform, while seemingly a minor detail, symbolizes this broader modernization effort – a visual representation of a force adapting to the demands of the 21st century.

Notes

(Notes are kept as in the original article)

1 China’s Military Strategy (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, May 2015), available at .

2 The Military Balance 1996/97 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1996), 179–181. In 2018, China’s officially announced defense budget was about 175 billion USD (based on exchange rates). For a useful discussion of the growth of the Chinese defense budget, see Richard A. Bitzinger, “China’s New Defense Budget: Money and Manpower,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), March 11, 2018, available at .

3 China’s National Defense in 2000 (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, October 2000), available at .

4 China’s National Defense in 2004 (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, December 2004), available at .

5 The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, April 16, 2013), available at .

6 China’s Military Strategy. Emphasis added.

7 “Xi Reviews Troops in Field for First Time,” Ministry of National Defense, July 30, 2017, available at . The Military Balance 2018 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2018), 250, estimates army personnel strength to be 975,000.

8 Both the 2006 and 2008 Chinese defense white papers described a “three-step development strategy” for defense modernization, which identified “mid-21st century” as the completion date for this process. The mid-21st century, or 2049, is also the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The three-step development strategy also provided two interim dates, or milestones: 2010 “to lay a solid foundation” and 2020 to “basically accomplish mechanization and make major progress in informationization.”

9 “China to Build World-Class Armed Forces by Mid-21st Century,” Xinhua, October 18, 2017, available at ; and “Xi Jinping: Build the People’s Army into a World-Class Military” [习近平:把人民军队全面建成世界一流军队], PLA Daily [解放军报], October 18, 2017, available at .

10 Feng Chunmei and Ni Guanghui [冯春梅, 倪光辉], “First Interview with Army Commander Li Zuocheng” [陆军司令员李作成首次接受媒体采访], People’s Daily [人民日报], January 31, 2016, available at.

11 As of September 2016, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) apparently has begun to use the term theater leader grade (zhanqu ji, 战区级) to replace the former military region (MR) leader grade. See “Military Training Units above the Level of the Deputy War-Level Units in the Army Held in Beijing” [全军副战区级以上单位纪委书记培训班在京举办], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 26, 2016, available at .

12 “China Names New Commanders for Army, Air Force in Reshuffle,” Reuters, August 31, 2017, available at .

13 PLA Navy headquarters has a Planning and Organization Bureau; therefore, it is logical that the army does also.

14 The names seen above continue to be reported as of March 2018. The Equipment Development Department “is mainly responsible for development and planning, [research and development], testing and authentication, procurement management, and information system construction for the whole military’s equipment.” See “MND Holds Press Conference on CMC Organ Reshuffle,” China Military Online, January 12, 2016, available at. Note there is no mention of repair and maintenance in that statement.

15 The first of these brigades has been identified in the Northern Theater Command (TC). See “Soldiers Operate Mobile Satellite Communication System,” PLA Daily, May 31, 2017, available at .

16 Liu Hongjun [刘洪军], “Strengthening Theater Army’s Innovation and Awareness of Warfighting and Construction” [强化战区陆军主战主建的创新意识], China Military Online [中国军网], May 10, 2016, available at .

17 Li Ming [黎明], “Chinese Communist Northern Theater PC Xu Yuanlin Removed from Office” [中共北部战区政委徐远林被免职 去向不明], New Tang Dynasty [新唐人], July 31, 2016, available at .

18 For example, Li Zuocheng worked with Bai Lu in the Chengdu MR, Liu Lei worked with He Qingcheng in the Lanzhou MR, and Liu Xiaowu served with Li Qiaoming in the 41st Group Army.

19 The “Two Inabilities” [liangge nengli bugou, 两个能力不够] are 1) our military’s ability to fight a modern war is insufficient, and 2) our cadres’, at all levels, abilities to command modern war is insufficient. The “Two Large Gaps” [liangge chaju henda, 两个差距很大] refers to gaps between the level of China’s military modernization and 1) the requirements for national security, and 2) the level of the world’s advanced militaries.

20 Li Zuocheng and Liu Lei, “Strive to Build a Strong and Modernized New-Type Army—Study Deeply and Implement Chairman Xi Jinping’s Important Discourse on Army Building” [陆军司令员政委:建设强大的现代化新型陆军努力建设一支强大的现代化新型陆军—深入学习贯彻习近平主席关于陆军建设重要论述], Qiushi [求是], February 15, 2016, available at .

21 Liao Keduo [廖可铎], “Promote Effective Army Transformation and Construction” [推进陆军转型建设落地见效], PLA Daily [解放军报], August 23, 2016, available at .

22 Wang Li and Yu Wei, eds. [王李, 宇薇], “One Extraordinary Assessment” [一次不同凡响的考核], PLA Daily [解放军报], January 22, 2015, available at . Xi has identified the problem as one the PLA must solve.

23 “MND Holds Press Conference on CMC Organ Reshuffle,” China Military Online, January 12, 2016, available at ; Wang Jun [王俊], “Beijing Garrison Has Been Transferred from the Former Beijing Military Region Army” [北京卫戍区已由原北京军区转隶陆军], The Paper [澎湃新闻], August 16, 2016, available at .

24 Zhang Baoyin [张宝印] et al., “Speed Up the Construction of a New National Defense Mobilization System with Chinese Characteristics” [加快构建具有中国特色的新型国防动员体系], Xinhua, March 9, 2016, available at .

25 “Jixi Jun Division Border Guard Officers and Men Turned to Donate Money before the Transfer of Education” [鸡西军分区边防部队官兵转隶交前倾情捐资助学], Bright Picture [光明图片], available at ; Meng Haizhong and Chen Youguang [孟海中, 陈宥光], “The Coastal Defense Forces Belonging to the Shantou Garrison Command in Guangdong Province Transferred Their Troops to the Army in February this Year” [广东省汕头警备区所属海防部队今年2月已转隶移交陆军], China National Defense Daily [中国国防报], April 1, 2017, available at .

26 “Northern and Southern TC Armies Forming Border Defense Brigades” [南部战区陆军, 北部战区陆军等均已组建边防旅], The Paper [澎湃新闻], May 9, 2017, available at .

27 “Brigade Party Members Carry Backpacks to Meetings” [旅党委委员背着背包来开会], PLA Daily [解放军报], January 10, 2018, available at .

28 Jing Runqiang [井润强], “Official Disclosure: Guangdong Reserve Division Transferred to the Army” [官方披露:广东某预备役师部队已转隶陆军], China National Defense Daily [中国国防报], April 7, 2017, available at .

29 Ma Hao Liang [馬浩亮], “Four Changes to Provincial Military Districts Leadership Positions Reduced” [省軍區四變化削減領導職務], Ta Kung Pao [大公报], April 24, 2017, available at .

30 Wang Jun [王俊],“Air Force Major General Zhou Li Transferred to Henan Provincial Military District Commander to Succeed Major General Lu Changjian” [空军少将周利调任河南省军区司令员,接替卢长健少], The Paper [澎湃新闻], April 12, 2017, available at .

31 The year 2020 is the deadline for the current phase of PLA reforms to be completed.

32 Liao Keduo [廖可铎], “Speed Up Building a Powerful Modernized New-Type Army” [加快建设强大的现代化新型陆军], PLA Daily [解放军报], March 29, 2016, available at .

33 The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, September 9, 2013), available at .

34 Order-of-battle details in this and following paragraphs are based on the author’s analysis of open Chinese sources; the numbers cited are close to, but not exactly the same as, the numbers found in the Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016 (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2016) and The Military Balance 2017 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2017).

35 The discussion of “below-the-neck” reform is based on and updates that found in Dennis J. Blasko, “PLA Army Group Army Reorganization: An Initial Analysis,” October 2017, available at Analysis.pdf>.

36 “Who Said There Is Trust Crisis? I Say Never Leave Any Brother” [你说有信任危机?我说绝不丢下任何一个兄弟], PLA Daily [解放军报], February 6, 2018, available at .

37 “Role Model Helps New Recruits Grow and Improve” [身边榜样助力新兵成长进步], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 30, 2017, available at . A new marine special operations forces (SOF) brigade with a Dragon Commando unit [jiaolong tuji dui, 蛟龙突击队] may also have been formed recently from existing marine assets. See “Decrypt ‘Operation Red Sea’ Prototype” [解密《红海行动》原型], Sina.com, February 20, 2018, available at .

38 “PLA Daily Commentator: Adhere to Training to Prepare for War” [解放军报评论员文章:坚持练兵备战], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 22, 2015, available at .

39 Zhang Tao, ed., “Type-96B Seen as Pillar of Nation’s Tank Force,” China Daily (Beijing), August 10, 2016, available at . The numbers cited in this article are roughly consistent with what has been reported by The Military Balance 2017 and U.S. Department of Defense 2016 report on the Chinese military. The 7,000 figure includes both main battle tanks and light tanks.

40 The Military Balance 2018, 251.

41 Zhang Zhaoxing [张照星], “Transformation of Combined Arms Battalion from ‘Accepting Instructions Type’ to ‘Independent Operations Type’” [合成营由“接受指令型”向“独立作战型”转变], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 9, 2016, available at ; and Wang Renfei and Zhang Xuhang [王任飞, 张旭航], “Combined Infantry Battalion Has Command Post” [合成步兵营有了“中军帐”], PLA Daily [解放军报], May 27, 2015, available at .

42 Yang Xihe and Kang Ke [杨西河, 康克], “20th Group Army Realizes Precision Command by Breaking Information Barriers Between Arms” [第20集团军打破兵种信息壁垒实现精确指挥], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 25, 2016, available at .

43 Ma Sancheng and Sun Libo [马三成, 孙利波], “Western Theater Army Units Hold Command Ability Standards Training” [西部战区陆军部队开展指挥能力达标集训], PLA Daily [解放军报], March 23, 2016, available at .

44 Yin Hang and Liang Pengfei [尹航, 梁蓬飞], “All Army Symposium on Realistic Military Training Held in Beijing” [全军实战化军事训练座谈会在京召开], China Military Online [中国军网],June 25, 2016, available at .

45 For a recent example of this goal stated in English, see Ouyang, ed., “Symposium Highlights Matching Military Exercises with Real Combat,” Xinhua, June 26, 2016, available at .

46 Jian Lin [菅琳], ed., “Lay Greater Stress on System-of-Systems Building” [更加注重体系建设], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 18, 2016, available at.

47 For two examples in 2016, see “For a Strong Military First Train Generals, in Training Soldiers Train Officers First” [强军先强将 练兵先练官], PLA Daily [解放军报], January 17, 2016, available at ; and “With This Type of Locomotive in the Lead, Are the Little Partners Living It?” [有这样的“火车头”领跑,小伙伴们还坐的住吗?], PLA Daily [解放军报], April 12, 2016.

48 Zhang Xudong [张旭东], “Grasp the ‘Key Links’ of Joint Operations” [抓住联合作战“关节点”], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 19, 2016, available at .

49 Jiang Yukun [姜玉坤], “The Battalion to Become the PLA’s Basic Combat Unit to Carry Out Independent Tasks” [营将作为解放军基础战术单元独立执行作战任务], Xinhua, April 25, 2008, available at .

50 Liao Qiaoming [李桥铭], “Let New-Type Combat Forces Become PLA’s ‘Trump Cards’” [让新型作战力量成为手中“王牌”], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 15, 2016, available at .

51 For a description of transregional exercises from 2006 to 2011, see Dennis J. Blasko, “Clarity of Intentions: People’s Liberation Army Transregional Exercises to Defend China’s Borders,” in Learning by Doing: The PLA Trains at Home and Abroad, ed. Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, and Travis Tanner (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2012), 171–212.

52 Liang Pengfei and Li Yuming [梁鹏飞, 李玉明], “Looking Back at Zhurihe, Seeing the Hardship” [回望朱日和,忧患之中见担当], PLA Daily [解放军报], August 21, 2014, available at .

53 Shao Min and Sun Xingwei [邵敏, 孙兴维], “Army Organizes 17 Transregional Exercises from July to September, Seven New Rules to Promote Realistic Confrontation” [陆军7至9月组织17场跨区演习 7条新规推动真打实抗], PLA Daily [解放军报], August 4, 2016, available at .

54 “2017 Army Unit Base Training Begins” [2017年陆军部队基地化训练拉开战幕], PLA Daily [解放军报], August 24, 2017, available at .

55 Shao and Sun, “Army Organizes 17 Transregional Exercises from July to September, Seven New Rules to Promote Realistic Confrontation”; ibid.

56 “Stride-2016 Zhurihe Series of Live Confrontation Exercises Begins” [跨越-2016•朱日和”实兵对抗系列演习拉开战幕], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 16, 2016, available at .

57 Zhang Li, Wu Aili, and Zhao Lingyu, “Exercise Mission Action-2013C Led by China’s Air Force,” International College of Defence Studies, People’s Liberation Army National Defense University, June 5, 2013, available at .

58 For joint exercises commanded by the navy and air force in 2014 and 2015, see Dennis J. Blasko, “Integrating the Services and Harnessing the Military Area Commands,” Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 5–6 (August 1, 2016), 685–708.

59 Li Mangmang [李芒茫], “ASEAN Joint Exercise Begins, Special Operations Force Participates” [东盟联合演练拉开帷幕 特战队员随队参加], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 6, 2016, available at ; Wang Ning and Sun Xingwei [王宁,孙兴维], “‘Peace Mission-2016’: Listen to the Soldiers! Blood Is Flowing!” [“和平使命-2016”:众将士听令!热血出征!], China Military Online [中国军网], September 12, 2016, available at .

60 Zhang Tao, ed., “PLA Sends Team for International Jungle Patrol Competition in Brazil,” China Military Online, August 11, 2016, available at ; and Zhang Tao, ed., “China Tops International Sniper Competition,” China Military Online, June 28, 2016, available at .

61 Zhang Tao, ed., “Two Events of International Army Games 2016 Held in Kazakhstan,” China Military Online, August 3, 2016, available at .

62 Zhang Tao, ed., “International Army Games 2016 Wraps Up in Russia,” China Military Online, August 15, 2016, available at .

63 “Aim, Race, Win! Russia’s Tank Biathlon 2016 in Most Spectacular Photos & Videos,” RT.com, August 14, 2016, available at .

64 “New Chinese Type-96B Tank Just Broke Down at ‘Tank Biathlon’ Competition,” Defence Forum India, August 15, 2016, available at .

65 Daniel Hartnett, “China’s First Deployment of Combat Forces to a UN Peacekeeping Mission-South Sudan,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 13, 2012, available at ; and “China to Send Peacekeeping Forces to Mali,” Xinhua, July 12, 2013, available at . Some sources call the deployment to Mali the “first” deployment of a guard force.

66 “Details of China’s First Peacekeeping Infantry Battalion,” China Military Online, December 23, 2014, available at .

67 Yao Jianing, ed., “2nd Batch of Chinese Peacekeeping Infantry Battalion Flies to South Sudan,” China Military Online, December 3, 2015, available at .

68 Dai Feng and Wu Xu [代烽, 吴旭], “Combat and Support Integration, a ‘Road’ That Must Be Crossed” [战保一体,一道非迈不可的“坎”], PLA Daily [解放军报], July 18, 2016, available at .

69 “83rd Group Army Organizes Equipment Backbone Training Mobilization Activity” [第83集团军组织召开装备骨干集训开训动员活动], PLA Daily [解放军报], March 22, 2018, available at ; “In Order to Get Work Results Examine the Effectiveness of Learning and Implementation” [以工作成果检验学习贯彻成效], PLA Daily [解放军报], December 10, 2017, available at ; “Fast Train and Mercedes Fusion in Tianshan North and South,” PLA Daily [解放军报], January 19, 2018, available at .

70 “More Than 10 Units Combine into a Brigade, Harmoniously” [10多个单位合编成一个旅,和谐相处有妙招], PLA Daily [解放军报], June 3, 2017, available at .

71 “China Establishes Joint Logistic Support Force,” China Military Online, September 13, 2016, available at .

72 Liu Jianwei [刘建伟] et al., “From ‘Department’ to ‘Force’: The Reforms Our PLA’s Joint Logistics Must Make” [从“部”到“部队”:我军联勤改革要跨越啥], PLA Daily [解放军报], April 18, 2017, available at .

73 Zhang Tao, ed., “Defense Ministry Holds News Conference on Joint Logistic Support System Reform,” China Military Online, September 14, 2016, available at .

74 Zhang Tao, ed., “PLA Restructuring Changes Focus at Military Schools,” China Daily, April 28, 2016, available at .

75 Zhao Yusha, “‘Solemn’ Retirement Ceremony Called for PLA Officers,” Global Times (Beijing), June 14, 2016, available at .

76 Yang Hong [杨红], ed., “From 2017, No More National Defense Students Will Be Recruited from Ordinary High School Graduates” [2017年起不再从普通高中毕业生中定向招收国防生], China Military Online [中国军网], May 26, 2017, available at .

77 Zhang, ed., “PLA Restructuring Changes Focus at Military Schools.”

78 Yao Jianing, ed., “PLA Adjusts Policies on Graduate Student Enrolment,” China Military Online, September 19, 2016, available at .

79 Yao Jianing, ed., “Xi Brings Strength, Integrity to Chinese Armed Forces,” Xinhua, July 30, 2016, available at .

80 Zhang Jiashua and Hai Yang [张佳帅, 海洋], “System of Systems Operations: Turn ‘Strong Fingers’ into a ‘Hard Fist’” [体系作战:变 ‘指头强’为 ‘拳头硬’], PLA Daily [解放军报], September 18, 2016, available at .