The chef uniform is more than just work clothes; it’s a powerful symbol of professional pride and culinary tradition. Across every walk of life, a uniform signifies dedication and belonging, but for chefs, it carries an even deeper significance. Donning the classic chef uniform – the toque, jacket, checkered pants, neckerchief, apron, and side towel – is stepping into a lineage that stretches back centuries. It’s a globally recognized standard of dress that instantly communicates expertise and skill to both industry professionals and diners alike. Beyond aesthetics, each component of the chef uniform is meticulously designed to ensure the wearer’s safety and comfort within the demanding kitchen environment.

At institutions like the Culinary Institute of America, the chef uniform is integral to the culinary journey. Students in Culinary Arts and Baking and Pastry Arts programs receive personalized chef jackets and pants, fostering a sense of belonging from day one. For kitchen classes, specific uniform elements like polished black leather shoes, a white neckerchief, apron, side towel, and toque are mandatory. Upon graduation, this journey is further commemorated with an “alumnus” jacket, marking their entry into a distinguished network of culinary professionals.

The modern chef uniform we recognize today is the result of generations of evolution, shaped by a blend of practical necessities and symbolic meanings. Four key factors have driven this evolution: the critical need for protection in a hazardous workplace, the aesthetic desire to project a clean and professional image, the aspiration to establish status and instill pride, and the unifying effect of a standardized dress code that minimizes individual differences and fosters teamwork. The chef uniform, therefore, embodies both the practical demands of the kitchen and the romantic allure of culinary tradition.

Historically, the apron served as the earliest identifier of a cook. Illustrations from the 15th century, such as those accompanying Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, depict cooks wearing aprons. By the Victorian era, chefs in white clothing and caps resembling nightcaps or tams-o-shanters became common in prints and illustrations. Even literary descriptions, like Thackeray’s portrayal of a chef in an 1852 story wearing a crimson velvet waistcoat and a white hat, contribute to the evolving image of chef attire.

Numerous stories and legends surround the origins of each part of the chef uniform, from the iconic toque to the specialized shoes.

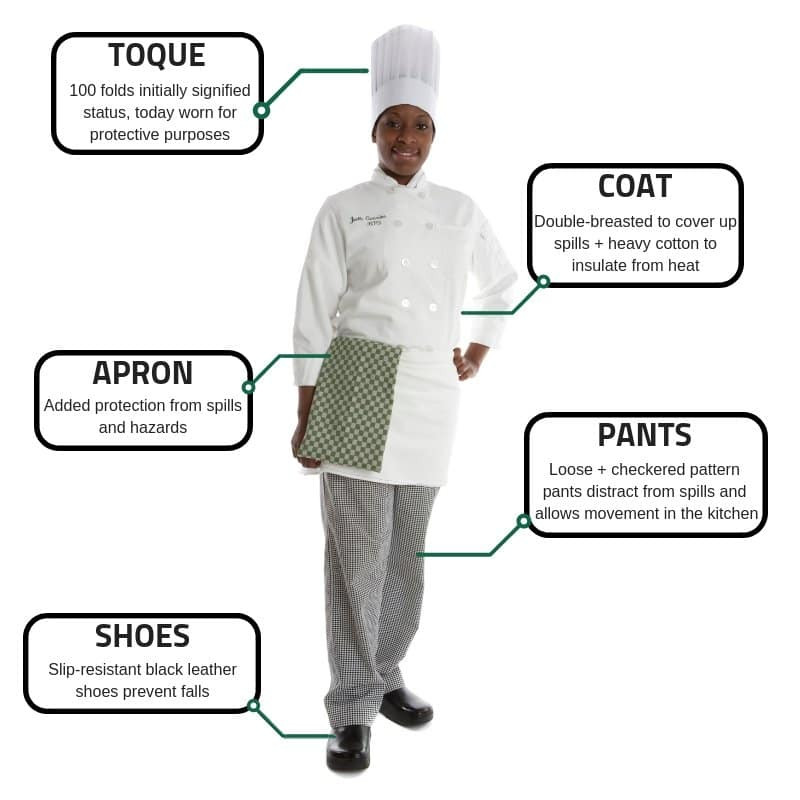

history-anatomy-chefs-uniform-infographic

history-anatomy-chefs-uniform-infographic

The Toque: A Crown of Culinary Expertise

The toque, or chef’s hat, boasts a history stretching back to ancient times. In Assyria, where poisoning was a prevalent threat to royalty, chefs were chosen from the most trusted subjects, sometimes even royal family members, and elevated to court status. These royal chefs, responsible for the king’s safety, received generous compensation and were permitted to wear crowns similar in shape to the royal headdress, but crafted from cloth and without jewels. This is believed by some to be the origin of the toque’s crown-like shape and pleated design. A popular legend suggests that the approximately 100 pleats in a traditional toque represent the countless ways a chef can prepare an egg – a story attributed to various ancient cultures including Persia, Rome, and France.

During the height of the Greek and Roman Empires, chefs commanding lavish feasts held positions of prestige and were ceremoniously “crowned” with bonnet-style caps adorned with laurel leaves before the royal court.

Another theory links the modern toque to the headdress of Greek Orthodox priests. As the Byzantine Empire fell to invaders in the 6th century AD, philosophers, artists, and cooks – considered of equal intellectual standing – sought refuge in Greek monasteries, disguising themselves as priests. Out of respect for the clergy, these culinary artists changed their hats from black to white, marking a significant shift in the toque’s color.

By the 16th century, regional variations in toque styles emerged across Europe. The French favored a flattened beret, Italians opted for a medium-height toque with formal pleats, and Germans preferred a softly gathered style.

Two centuries later, French chefs were seen wearing the “casque à méche,” a stocking cap, with color indicating rank. Simultaneously, Spanish cooks donned white wool berets, while German chefs sported pointed Napoleonic hats with tassels.

In England, black hats were the norm for cooks. British Baronial cooking, prevalent in the Middle Ages, involved preparing massive roasts over open wood-burning hearths. Chefs spent extended periods tending these fires, accumulating soot and ash on their hats. Black hats, therefore, served a practical purpose. These caps were often pressed flat, enabling chefs to carry food from distant kitchens to dining areas.

Well into the 20th century, English cooks continued to wear small black hats resembling librarian skullcaps. Impractical for regular stove work and lacking in comfort, this headgear evolved into a symbol of the “master cook” or kitchen supervisor.

During Napoleon III’s reign (1808–1833), it’s said that bald cooks were required to wear velour or heavy cloth caps, while those with hair wore linen or netting, highlighting early considerations for hygiene and practicality within the chef uniform.

In the early 19th century, Chef Boucher, serving the Prince of Talleyrand, mandated white toques for his entire kitchen staff for sanitary reasons. The white toque effectively contained hair, preventing contamination, and absorbed perspiration, enhancing hygiene and comfort. Furthermore, the air pocket within the tall toque provided insulation, helping to keep the head cool in a hot kitchen environment.

Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935), a pivotal figure in modern cuisine, championed the tall, starched, and pleated white toque, known as “La Toque Blanche,” for its comfort and commanding presence. Initially, pleats were sewn into the fabric; later, starch provided stiffness. Despite “toque” being the French word for a soft, brimless hat, the term stuck.

Escoffier famously stated, “A cuisinier is judged worthy to wear La Toque Blanche only through his perfect workmanship.” He further standardized toque heights to signify kitchen hierarchy, allowing for instant recognition of rank within the culinary brigade.

Marie-Antoine Carême, while serving as chef to the English Ambassador to Vienna, Lord Stewart, is credited with popularizing the starched high hat. He inserted a round piece of cardboard into a flattened, starched toque, a style illustrated in his 1822 book Le Maître d’Hôtel. This fashion rapidly gained traction in Vienna and Paris, though it remained less common among British cooks until the 20th century. Carême’s work significantly promoted the elements that constitute the modern chef uniform.

Alfred Suzanne, author of La Cuisine Anglaise (1894), pinpointed 1840 as the year the toque replaced bonnets and berets in kitchens. However, he personally found the toque “as ridiculous as uncomfortable,” and criticized the “Eiffel Tower” style toque as vulgar, favored by those seeking to appear taller and more imposing to subordinates.

Today, executive chefs often wear toques reaching approximately 12 inches in height, while apprentices and amateur cooks wear 8-inch toques. As recently as the 1960s, toque manufacturers maintained detailed records of chefs, including height, weight, hat size, and kitchen rank, enabling them to create perfectly tailored toques upon request, reflecting the personalized nature of the chef uniform even in its standardized form.

Harold McGee, in The Curious Cook, suggests a practical advantage of baseball caps over toques: a visor can prevent oil droplets from settling on a chef’s glasses, a testament to the ongoing evolution of headwear in response to kitchen needs.

The Jacket: Functionality and Professional Presentation

The double-breasted chef jacket, featured in Marie-Antoine Carême’s 1822 illustrations, became widely fashionable by 1878, when Angelica Uniform Group began its manufacture. The ingenious wide-flapped design offered a practical advantage: if the front became soiled, the flaps could be reversed, concealing the stain and maintaining a presentable appearance. This doubled the wear time and provided two layers of fabric for enhanced protection against spills, splashes, heat, and steam – crucial elements in a demanding kitchen.

The jacket’s reversible button closure makes it suitable for both men and women. This unisex design reflects the modern understanding that “chef” is a profession irrespective of gender, and the chef uniform should be inclusive.

The longer sleeves of the chef jacket are another functional design element. They offer arm protection from burns when reaching into hot ovens and can be quickly used as makeshift oven mitts to handle hot cookware, demonstrating the practical ingenuity embedded within the chef uniform.

The Side Towel: A Multi-Purpose Kitchen Essential

In contemporary kitchens, side towels are indispensable for chefs, primarily used to protect hands when handling hot pots and pans. When not in use, the towel is typically tucked into the apron string for easy access. It’s important to note that the side towel is not intended as a general wiping cloth. If a spill is instinctively cleaned with the side towel, it must be replaced immediately, as even slight dampness compromises its insulation properties. A wet side towel conducts heat rapidly, increasing the risk of burns.

The Apron: Shielding the Uniform and Enhancing Hygiene

Worn over the jacket and torso, the apron serves a dual purpose: protecting both the chef and the chef uniform. Historically, aprons were vital safety garments, shielding chefs from open flames. Today, they primarily protect the jacket and pants from spills, scalds, and stains, maintaining a clean and professional appearance. An 1892 London cookery class instructed apprentices on apron etiquette: “Reversing the apron once is permissible, and stains can be concealed by adjusting folds.” However, instructors cautioned against excessively short aprons, emphasizing the balance between practicality and professional presentation within the chef uniform.

The Trousers: Camouflage and Practicality

Chef trousers typically feature a small checkered pattern, ingeniously designed to conceal inevitable kitchen stains. In the United States, black and white houndstooth is common, while European chefs often prefer blue and white patterns. This practical design element contributes to maintaining a consistently professional appearance, even amidst the challenges of a busy kitchen.

The Shoes: Foundation of Comfort and Safety

Often overlooked, high-quality, supportive, and protective footwear is a critical component of the chef uniform. Anyone spending long hours on their feet in a kitchen understands this importance. Durable leather shoes with slip-resistant soles are recommended for both protection and support.

The New Professional Chef, published by the Culinary Institute of America, advises taking time to try on various shoe styles to find the most suitable fit and comfort level. Neglecting foot health can lead to foot pain, back problems, and long-term discomfort. Seeking professional advice and considering orthotics are recommended for chefs experiencing foot issues, emphasizing the importance of proper footwear as part of the chef uniform.

The CIA also emphasizes that sneakers or athletic shoes are inappropriate in the kitchen. While comfortable, they lack the necessary protection against sharp objects and hot liquids, highlighting the safety-focused design of professional chef shoes.

The Neckerchief: Functionality and Finishing Touch

The neckerchief, tied cravat-style, adds a finishing touch to the chef uniform, similar to a necktie in business attire. Historically, in sweltering kitchens, the neckerchief absorbed facial perspiration. It also served a medical purpose, protecting the neck and throat from extreme temperature fluctuations between hot stovetops and cold storage areas. These temperature swings could lead to illness, from colds to pneumonia, underscoring the practical origins of the neckerchief.

While some modern chefs explore variations in uniform colors, the classic white chef uniform remains a symbol of cleanliness and purity, projecting a desirable image to diners. Although toque usage may vary among chefs, Roger Fessaguet, former owner of La Caravelle and president of Vatel Club, aptly compares it to a policeman’s hat: “Could you think of a policeman without a hat? That is part of the full uniform. It’s a sign of respect for the chef.”

Cotton remains the preferred fabric for chef uniforms due to its comfort in hot kitchen environments and its durability to withstand frequent laundering.

Proper laundering is the final, crucial aspect of the chef uniform. Jackets and pants should be washed daily after each shift. Aprons and neckerchiefs require more frequent changes if soiled. Maintaining a pristine white and sanitary jacket is paramount, as clothing can harbor bacteria and other contaminants that pose a food safety risk.

Wearing a clean and crisp chef uniform at the start of each day reflects pride in one’s appearance, skills, and profession. More importantly, it demonstrates a commitment to hygiene and the health of customers. The chef uniform signifies membership in a team and dedication to a noble and time-honored culinary craft.

Envision Yourself in a Chef Uniform?

Discover how the CIA can help you turn your passion for food into a fulfilling career.