The uniforms worn by soldiers often tell a story of their time, reflecting the conflicts, alliances, and transformations of an era. While discussions of military attire frequently center on combat uniforms, the narrative of World War 1 Italian Uniforms extends into the less-discussed but equally significant roles played during World War II. This is exemplified by the Italian Service Units in the United States, formed by Italian prisoners of war (POWs) who, despite their initial status as enemies, became a vital support force. Their uniforms, though American, bore the insignia of their origin, subtly echoing the military heritage that included the battlefields of World War I.

In November 1942, following the Allied forces’ successful campaign in North Africa, the United States received over 51,000 Italian POWs, housing them in camps across the country. This situation evolved dramatically after September 1943, when Italy, under General Pietro Badoglio, who had taken power after the arrest of Benito Mussolini, surrendered to the Allies. Italy then declared war on Germany in October 1943, transforming the perception of Italian POWs in American eyes. No longer seen solely as enemies, they were viewed as potential allies in a changing global landscape.

Italian Service Unit Receiving Supplies, Boston Port of Embarkation, South Boston, Massachusetts. Italian POWs in American uniforms with "Italy" patches receive supplies, highlighting their transition from enemy to ally during WWII.

Italian Service Unit Receiving Supplies, Boston Port of Embarkation, South Boston, Massachusetts. Italian POWs in American uniforms with "Italy" patches receive supplies, highlighting their transition from enemy to ally during WWII.

This shift in perspective led to the creation of the Italian Service Units (ISUs) in February 1944. The U.S. Army Service Corps offered Italian POWs the opportunity to volunteer for these units. Those who joined were given various jobs, received monetary compensation, and were granted increased freedom of movement. Volunteers pledged allegiance to the new Badoglio government and underwent screening to ensure they were not pro-Fascist, a necessary step in integrating former enemy soldiers into a supportive role.

The response was significant. Out of the 51,000 Italian POWs in the United States, over 45,000 chose to join the Italian Service Units. These units were deployed across the United States to areas experiencing labor shortages, filling critical gaps in various sectors. The remaining POWs, those who did not volunteer or were considered pro-Fascist, were moved to more isolated camps, primarily in Texas and Arizona.

Each Italian Service Unit comprised between 40 and 250 men, commanded by an Italian officer. These units worked alongside both military and civilian personnel, providing essential support to agriculture, hospitals, Army depots, seaports, and Army training centers. Reflecting their unique status, members of the ISUs were issued American uniforms, but with distinct Italian Service Unit insignia and badges. This uniform subtly acknowledged their Italian identity while integrating them into the American logistical framework. While not directly related to World War 1 Italian uniforms in design, the insignia served a similar purpose – distinguishing Italian military personnel, albeit in a drastically different context.

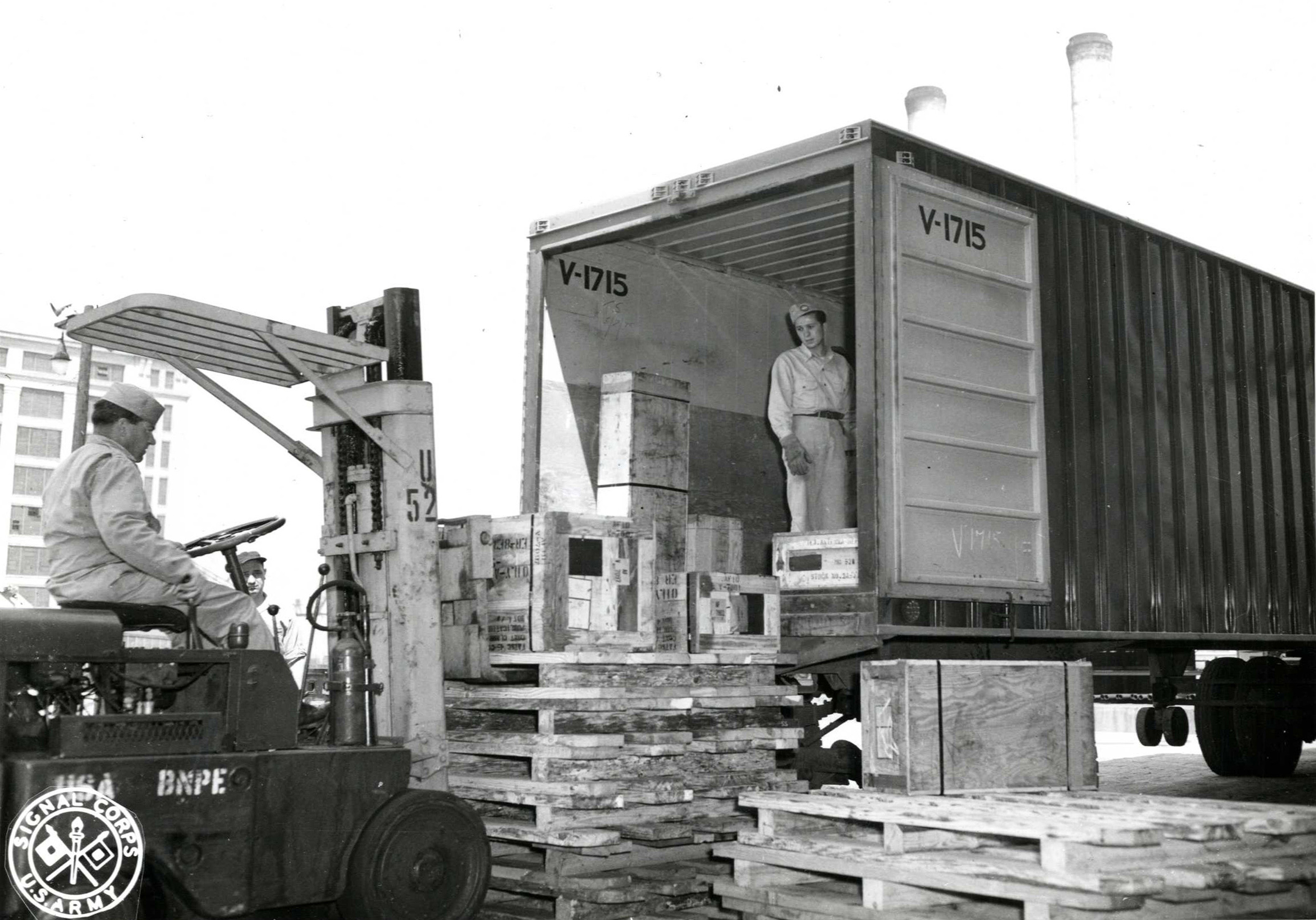

Italian Service Unit receiving supply of beer via railroad car, Boston Port of Embarkation, South Boston, Massachusetts. Italian Service Unit members are pictured receiving a supply of beer, illustrating the improved conditions and morale within these units during World War II.

Italian Service Unit receiving supply of beer via railroad car, Boston Port of Embarkation, South Boston, Massachusetts. Italian Service Unit members are pictured receiving a supply of beer, illustrating the improved conditions and morale within these units during World War II.

Approximately 3,000 Italian prisoners were held in camps in and around Boston, Massachusetts, and a substantial number of these men joined the service units. Although officially still classified as POWs, they wore American uniforms distinguished only by an “Italy” patch. This patch was worn on the left sleeve and affixed to the standard garrison cap, a simple yet powerful symbol of their changed role. This visual modification to the standard US uniform was a far cry from the distinct and sometimes elaborate designs of World War 1 Italian uniforms, yet it served a crucial purpose in identity and recognition within the WWII context.

In addition to uniforms, the Italian service members received a monthly stipend of $24. However, only one-third of this was paid in cash; the remainder was issued as script, usable at the base canteens for supplies and personal items. This system provided for their basic needs and a few comforts while still maintaining a degree of control over their economic activity.

An article in the May 15, 1944, edition of the Boston Globe highlighted an Italian Service Unit working in Franklin Park, Boston, noting it as the first such unit employed in the country. The Globe reported, “The men wear American Army uniforms carrying the insignia of ‘Italy’ and are supervised by Italian officers, and we believe is the first unit employed in such work.” This public acknowledgment marked a significant step in recognizing the ISUs’ contribution to the American war effort.

The presence of Italian POWs, and particularly the ISUs, in the Boston area drew considerable attention from the local Italian American community. Thousands of Italian Americans visited the low-security camps and work sites, seeking news of relatives and hometowns. The influx of visitors became so large that the Boston police had to assign military police details to manage the crowds of information seekers, demonstrating the strong community ties and the human dimension of this wartime situation.

The primary responsibility of the Italian prisoners in Boston was loading combat materials at the South Boston Army Base Port of Embarkation for shipment to the European theater. However, their work was diverse, including park maintenance and road construction throughout the Boston area. This labor was invaluable, freeing up American personnel for other critical tasks directly related to combat.

Italian Service Unit palletizing a supply of beer being unloaded from a railroad car at the Boston Port of Embarkation. South Boston, Massachusetts, Marine guard stand watch. Italian Service Unit members handle supplies under the watch of a Marine guard, showcasing the cooperation and security measures at the Boston Port of Embarkation during WWII.

Italian Service Unit palletizing a supply of beer being unloaded from a railroad car at the Boston Port of Embarkation. South Boston, Massachusetts, Marine guard stand watch. Italian Service Unit members handle supplies under the watch of a Marine guard, showcasing the cooperation and security measures at the Boston Port of Embarkation during WWII.

Beyond logistical support, the Italian Service Units also contributed to Boston’s Victory Garden on the Boston Common, further integrating them into the fabric of local wartime efforts. Life in the camps around Boston offered a respite from the direct conflict of war. The men enjoyed nightly movies, canteens stocked with Italian specialties, and a sense of safety. They even participated in their own guard duty, with occasional checks by American post guards, indicating a level of trust and autonomy.

Weekends brought two-day passes to Boston for ISU members on rotation. Local Roman Catholic churches played a crucial role in providing social and community support, hosting Sunday dinners with Italian families who prepared traditional Italian meals. The Catholic Church became a vital social outlet, offering Mass in Italian and parish hall gatherings that fostered a sense of belonging and welcome.

In Boston, a committee of Italian Americans, led by lawyer Frank W. Tomasello, collaborated with the American command to oversee the prisoners. This committee facilitated leaves and passes for recreational activities, further enhancing the quality of life for the ISU members. Brigadier General Calvin Dewitt, commanding officer of the Boston Quartermaster Depot, praised the performance of the service units as “more than satisfactory,” underscoring their effectiveness and reliability.

Despite some initial concerns from Boston residents about supervision levels, General Dewitt reassured the public, stating, “in order that essential work be carried out, the War Department has made available prisoner of war units . . . and their labor is essential. These men are contributing a great deal to the American war effort!” He emphasized the friendly relations between the Italian service members, American civilian workers, and soldiers, highlighting the positive integration and collaboration at the Port.

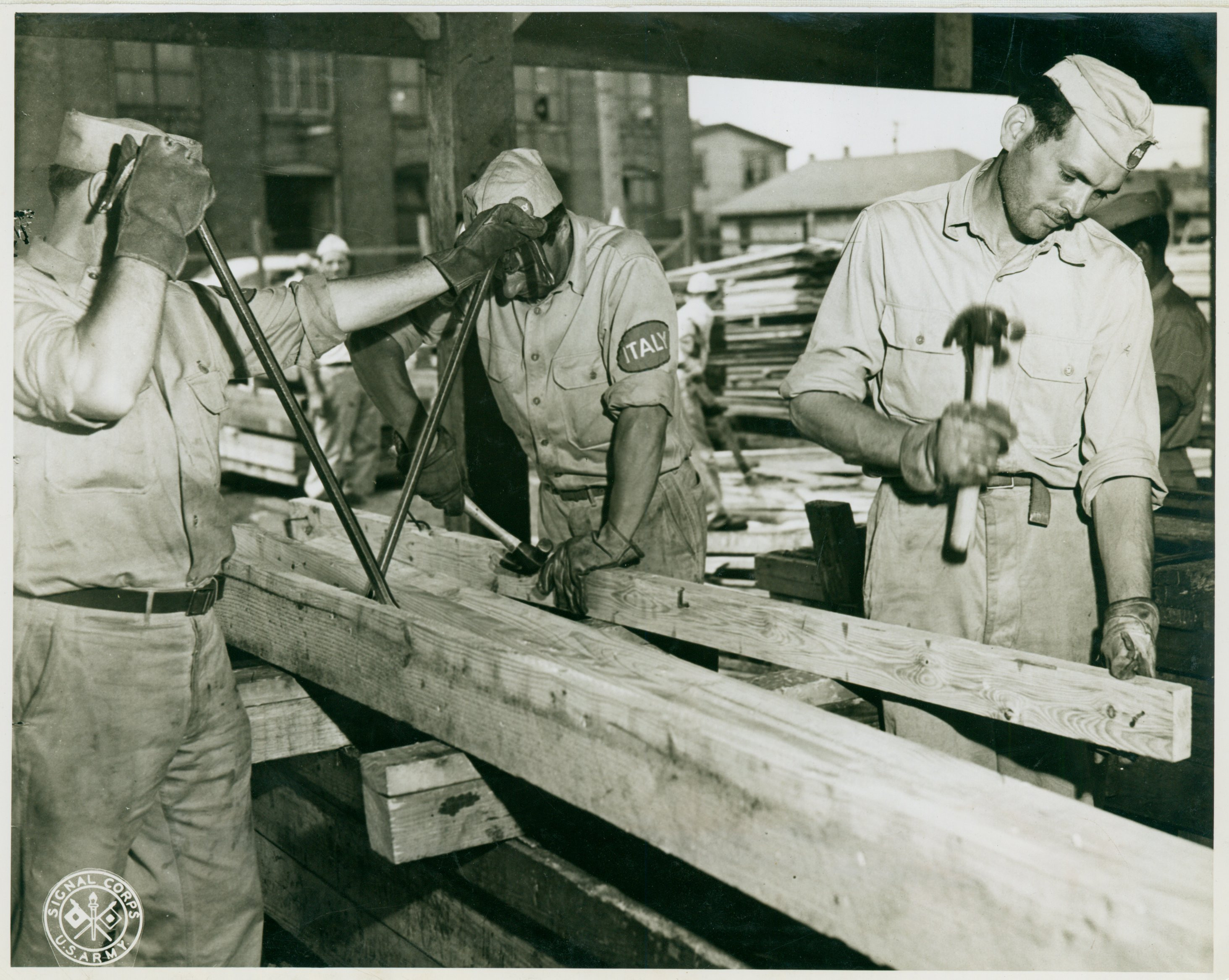

In August 1944, General DeWitt allowed media access to the Italian Service Units working in the harbor. A Christian Science Monitor reporter observed the Italians working “industriously, willingly and intelligently at freight handling, maintenance of equipment, and lumber salvage.” General DeWitt reiterated the importance of their labor, stating, “A short period back this port would have had difficulty in operating without them, and at the present moment their labor is badly needed.”

As the war concluded in August 1945, repatriation of the Boston-area Italian Service Unit soldiers began shortly after August 8, 1945, with the majority returning to Italy by December 1945.

Italian Prisoner of War (POW) lumber salvage workers, 1944. Italian POWs engaged in lumber salvage work, demonstrating the diverse labor contributions of the Italian Service Units within the United States during World War II.

Italian Prisoner of War (POW) lumber salvage workers, 1944. Italian POWs engaged in lumber salvage work, demonstrating the diverse labor contributions of the Italian Service Units within the United States during World War II.

The Italian Service Units collectively accounted for over 90 million-man days of labor in the United States between 1943 and 1945. Financially, the program saved the U.S. government an estimated $230 million. Furthermore, the ISUs freed up American soldiers from support roles, enabling them to serve in combat positions. This contribution indirectly impacted the draft, potentially reducing the number of American men required for military service. The program’s security issues were minimal compared to its significant productivity.

In recognition of their service, Italian Service Unit members were offered the opportunity to become U.S. citizens. Thousands accepted this offer, choosing to remain in the country that had once held them as prisoners but had also offered them a path to a new life. For those who chose repatriation in January 1946, their return to Italy was bittersweet. They left behind newfound friendships in Boston, returning to a homeland marked by the devastation of war. The story of the Italian Service Units is a remarkable chapter in World War II history, illustrating themes of transformation, cooperation, and the unexpected roles played by former adversaries, even in the uniforms they wore, subtly linked to a heritage that included the era of World War 1 Italian uniforms.

Sources

Calamandrei Camilla, Prisoners in Paradise: Italian POWs Held in America During WW II: A Historical Narrative and Analysis, 2012, https://www.prisonersinparadise.com/.

Conti Giovanni Flavio and Alan R. Perry, “Italian Prisoners of War in the Boston Area During World War II, The Italian American Review, Vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 2019), University of Illinois Press, p. 179.

“Former Italian War Prisoners at Work Here,” Daily Boston Globe (1928–1960); 15 May 1944, p. 1.

Conti, “Italian Prisones of War,” p. 184.

“War Prisoners Work on Docks Due to Labor Pinch, Army Says,” Daily Boston Globe (1928–1960); 2 August 1944; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872–1982), p. 7.

“Italian Prisoners and the Port of Embarkation.” The Christian Science Monitor, The Christian Science Monitor World Service, August 3, 1945, pg. 6.

Elizabeth Vallone, “Italian Prisoners of War in the United States,” L’Idea Magazine, March 10, 2015, http://lideamagazine.com/italian-prisoners-of-war-in-the-united-states